Ranjo, master Japanese bamboo flute maker, with Daniel and Kaoru

photo credit: Daniel Torres

Ranjo flutes I'm currently using

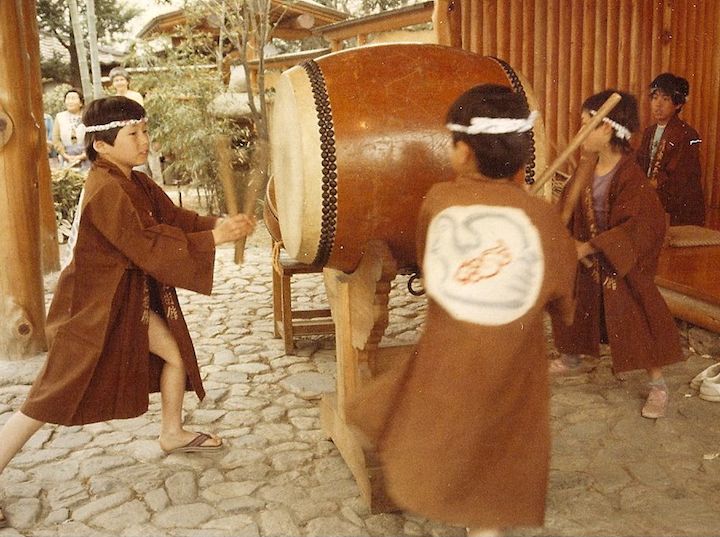

My first experience with a Ranjo shinobue (horizontal Japanese flute made from shino bamboo) was more than 10 years ago, when I bought a number 6 flute from Kaoru Watanabe. I started playing fue seriously upon moving to Honolulu in 2001 for graduate work at the University of Hawaii and to play taiko with Kenny Endo. Since that initial introduction, my fue collection has grown and I have had the opportunity to visit Ranjo san's workshop multiple times. Visiting him is always a wonderful experience, not only because I can play and handpick any flute in the shop, but especially because of the opportunity to see him work, ask questions, and experience his warm enthusiasm and complete dedication to his craft. My musicianship has grown largely due to Ranjo san's high-quality instruments and knowing him personally. Kaoru also continues to support me and provides constant inspiration. He introduced me to Daniel Torres last year because of our common interests, and I wanted to feature his thoughts and photographs on this blog. I asked both of them 5 questions.

Daniel Torres interview

photo credit: Daniel Torres

When and where did you first meet Ranjo san?

I met Ranjo san for the first time on June 2013, thanks to Kaoru san, who was kind enough to make the necessary introductions. I spent a whole day photographing him at his workshop in Chiba.

What makes his flutes special?

There are at least two things that make Ranjo san's flutes special. First, his hearing and sense of tuning is extremely accurate, and since the tuning of a fue is done by hand, he has the required skills to create very precise instruments. Second, his craftsmanship has been perfected over more than forty years of practice, so there is almost no compromise between form, aesthetics, and function. Ranjo san is quite ingenious when it comes to his crafting techniques and he is constantly improving upon his own designs. Kaoru can describe some of this better.

How can someone order a Ranjo fue?

I believe Kaoru san is the only person that sells Ranjo fue in North America. In Tokyo, you can go to Mejiro (a well known shinobue and shakuhachi store located near the station of the same name) and place an order.

What advice do you have for fue students?

Practice every day. There is no substitute for dedication and discipline. It is going to take a long time, it is going to take a lifetime. Sometimes it will be frustrating, but every now and then you'll have moments when it will be clear that you are going somewhere. Get used to playing in public as early as possible. Look for a mentor that can correct your technique as often as possible.

How can people learn more about Ranjo san?

Through Kaoru, perhaps? That is a bit of a difficult question. People who play fue know Ranjo through his craft, but to get to know him personally, you'd need to have access to him. Ranjo san is an amazing person, extremely generous, humble, and easy going. Perhaps some day we could convince him of doing a talk about his own life as a fue maker?

Daniel Torres

About me:

I'm a video game programmer, sake brewer, and occasional photographer. I've been studying fue for about three years so far, and played Taiko for about ten years as member of Kita no Taiko in Edmonton, Canada. My photography page can be reached at http://photography.dantorres.net, and my sake blog is http://sake.dantorres.net.

Kaoru Watanabe interview

photo credit: Daniel Torres

When and where did you first meet Ranjo san?

I met Ranjo san the first time while I was on tour with Kodo in the early 2000. Either I visited his studio as a young member of kodo or perhaps he came to the concert hall where we were performing.

What makes his flutes special?

The quality of material, the quality of craftsmanship are, first of all, superior to other flutes. He does certain things while making his fue that most others don't do - such as obsessing over the intonation of the overtone series and octaves. He has a curiosity and love of experimentation that propels him to improve upon his technique, even after nearly four decades of making fue. He once recreated a Polynesian nose flute I showed him but using aged bamboo and Japanese urushi.

How can someone order a Ranjo fue?

Contact me if you don't speak Japanese or contact him directly by phone or letter. He is a very friendly person. Also, his wife and daughter both speak a bit of English as well.

What advice do you have for fue students?

Listen to and try to imitate as many different styles of fue playing you can, even if you don't know what's going on. Listen to the music of noh, gagaku, kabuki, minyo, nagauta, various festival and folk musics, and shakuhachi music. This all of course is if you don't have access to someone who knows about traditional fue playing. Don't worry as much with the music of contemporary taiko groups in my opinion. It's difficult to make the shinobue sound like a Japanese instrument, as opposed to a vaguely "Asian" sounding instrument - so I strongly encourage people to study and listen to the traditional music (if that's what they're trying to do).

Kaoru Watanabe

How can people learn more about Ranjo san?

Just like studying Japanese music in general, nothing can compare to going to the source. To visit his workspace is to see first hand what it means to strive for pure perfection. To see him make fue and ask him questions about the process is always incredibly inspirational to me. I've had lessons and worked with many of the great fue players around but I've learned from him as much as any of them. His generosity and support of my career cannot be overstated. I have vowed to continue to strive to improve my playing with the same fervor that he strives to improve his fue.

2010 visit to Ranjo workshop

2013 visit to Ranjo workshop, with Shoji, Maz, Yasuo