Video: Five Study Tips for Taiko Players

A few months ago I was asked to submit a video for the Taiko Community Alliance Taikothon 2018, a one-day online event where videos from taiko artists and groups are broadcasted for public viewing. Typically, the videos contain live performances, discussion on a topic, or even skits (I especially enjoyed the creativity and production quality of Zenshin Daiko’s submission). Two years ago, I made a video explaining my approach to the rules of rhythm by breaking down the notion of pulse and subdivisions. This year I decided to contribute my top five tips - practices which have most significantly helped my development as a taiko player. Below is the video, which covers these tips and demonstrates them in an example where I play a hip Edo Bayashi atarigane transcription along to a cool funk tune. My top five study tips for taiko players are:

Think like a drumset player - good drumset players prioritize consistent timekeeping and being good accompanists. This means that we are always working on tempo control and playing with appropriate dynamic levels. Listening and flexibility are crucial ingredients for good accompanying.

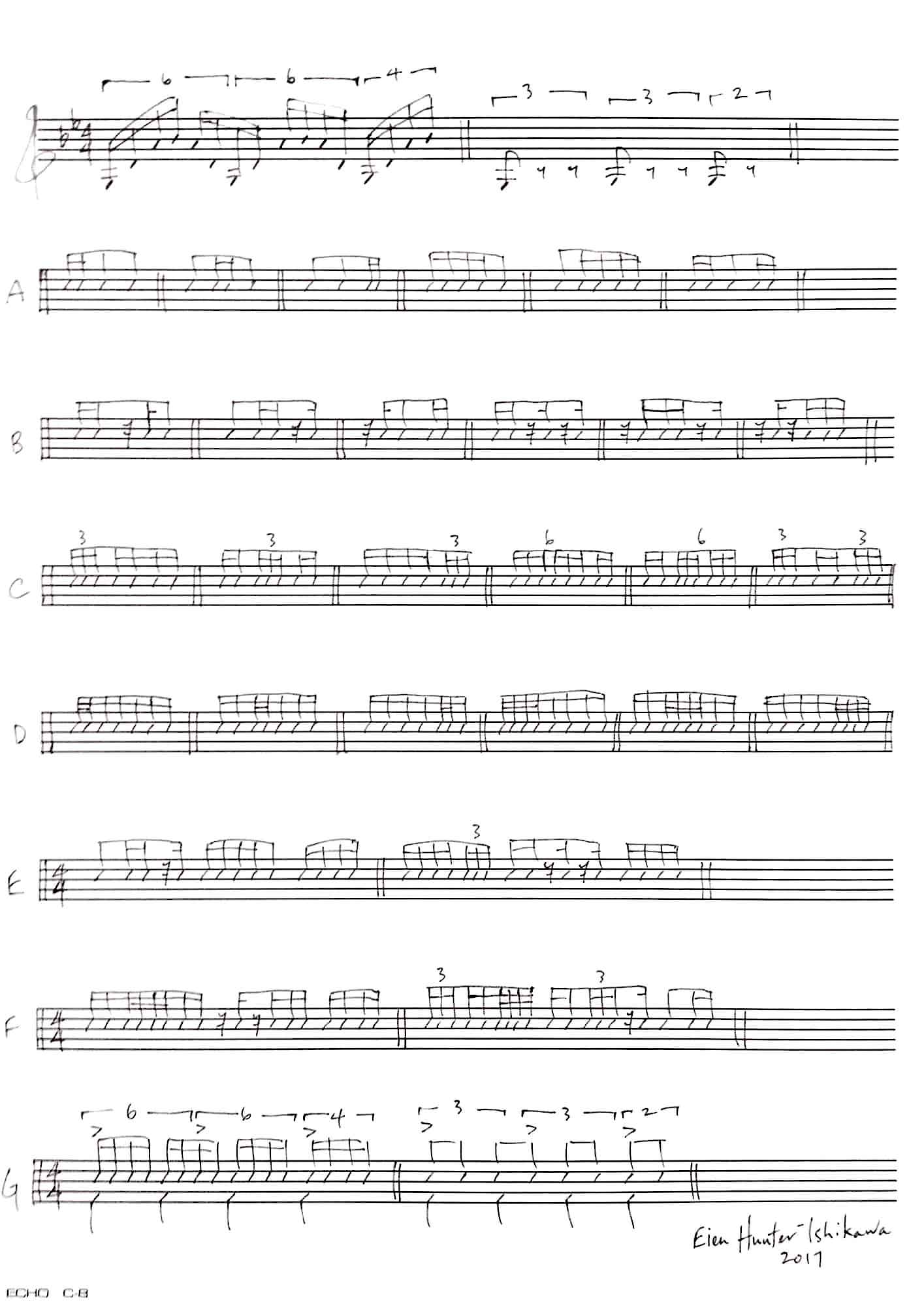

Transcribe music - students of jazz commonly transcribe and learn to play the solos of their favorite musicians. Not only does this practice teach you what kind of notes to play, it provides invaluable insight into why those notes are played and the phrasing (inflection) used to bring them to life.

Study traditional music - there is no substitute for experiencing the depth of an art form with centuries of history. When healthy, traditional music is full of life, constantly changing due to the cycle of practitioners keeping the best parts and removing the worst parts. There is a reason for everything contained in traditional music, and this is powerful.

Focus on your sound - the sound of your instrument is the most uniquely personal part of playing music. Trying to emulate your teacher’s sound or your favorite musician’s touch on the instrument is the path that will lead you to improving your sound.

Take private lessons - just like the clear difference between rehearsing with your group and practicing on your own, studying privately with a good teacher will greatly accelerate your development compared to learning in classes or workshops. Private lessons should have a laser focus on your goals, and a good teacher will provide the tools for you to reach them as long as you put in the work.

When I was asked to submit a video for the TCA Taikothon 2018, I decided to present these five ideas for improving musicianship. Find more ideas here: https://www.eienhunterishikawa.com/articles/