Shimedaiko Rope Types and How to Choose One

Shimedaiko rope used for testing

This guide is for anyone looking for information about shimedaiko rope. I prefer using the traditional rope-tightened style of shimedaiko over the bolted kind for several reasons:

They sound better to my ears.

They look better to my eyes.

They feel better to my arms when I carry them.

They are kinder on my stands, floors, limbs, and any surface that comes in contact with the drum.

They are still the only type used by professionals in many traditional arts such as kagura, noh, kabuki, and Edo Bayashi.

Obviously, the bolt-style drums are legitimate and have many fans, mainly due to the ease of tightening and loosening the drum quickly and evenly. To tighten properly, both drum styles require lots of practice and careful attention to detail to get the best sound and longevity of the instruments. I believe that rope shimedaiko can be more fun, rewarding, and beneficial to your growth as a player once you gain the knowledge and develop the skills required to care for it correctly. This blog entry is only about rope types, so send me an email if you are interested in learning more about the advantages of the wooden mallet tightening technique described here:

https://www.eienhunterishikawa.com/blog/my-favorite-shimedaiko-tightening-met

Kuremona (9mm)

Vintage 3 strand (10mm)

When I started my research about rope options for shimedaiko, I was surprised at how little information I could find online. There is a huge variety of rope types out there and this overabundance of choice is confusing when you are trying to compare materials, pricing, diameter, color, stretch, and the ability to hold knots. Hopefully this guide will help you narrow down the sea of choices and focus your own quest for the best rope. A special thanks to Chris Huynh for helping with my research.

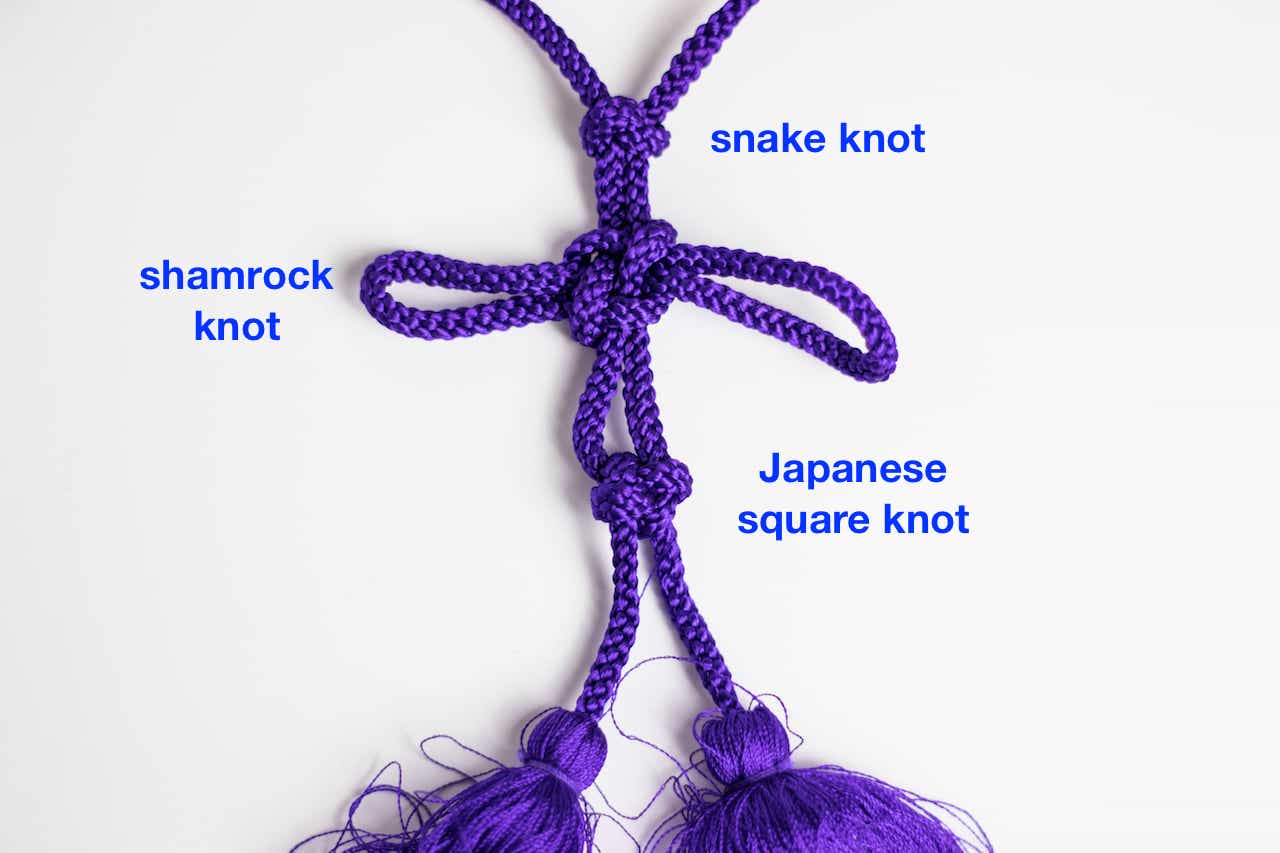

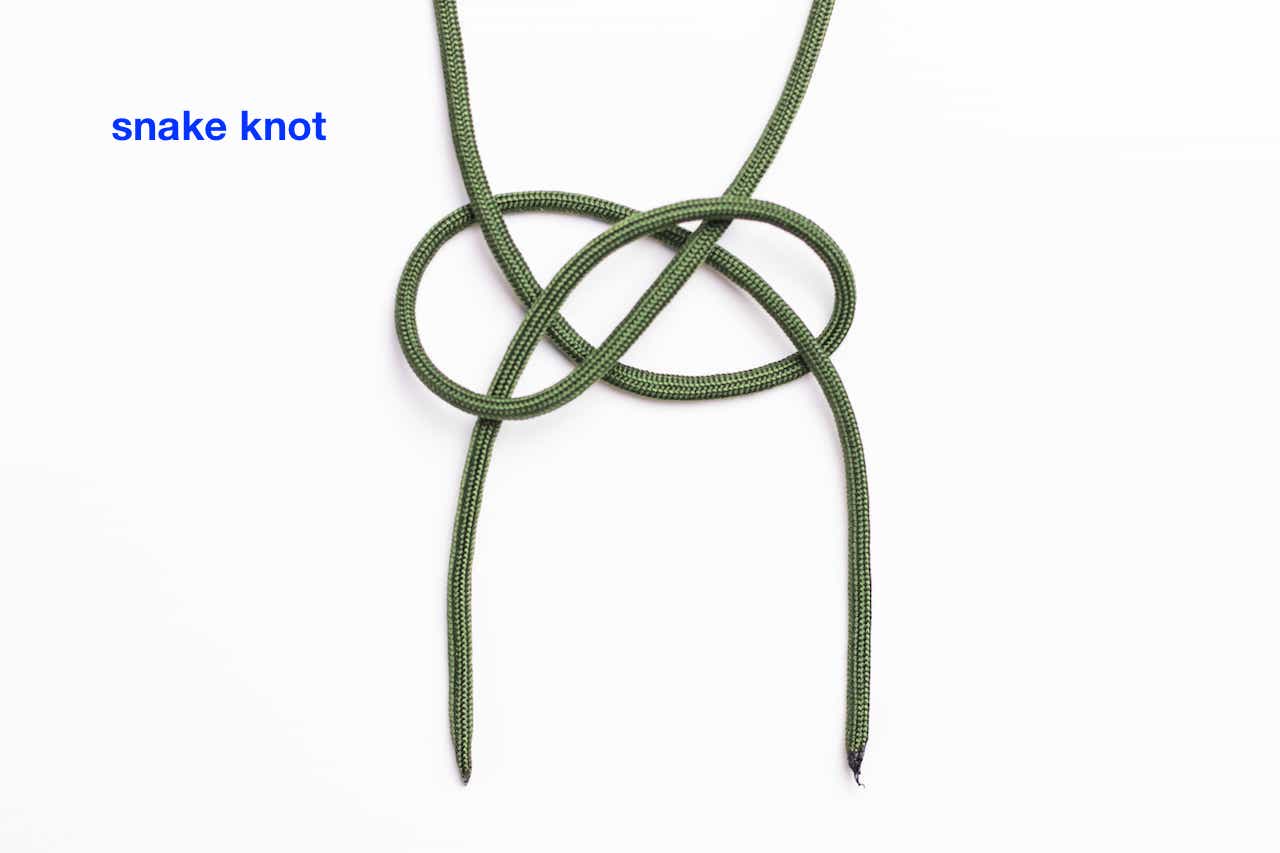

The two most important characteristics for shimedaiko rope performance are: not stretching and not slipping. The rope needs to hold knots during tightening, and then hold the tension after the drum is tightened. With these requirements in mind, here are the ropes I eliminated from my list of acceptable materials:

Nylon - too stretchy, too slippery

Cotton - too weak, too stretchy

Sisal - too hard, brittle, and rough

Kevlar - no good options available

Dyneema - too slippery

Spectra - too slippery

Hempex & Unmanilla/Promanilla - these are said to stretch and slip, but I haven’t tried it

Any braided rope - too smooth, and therefore too slippery

Below are the ropes that work, with pros and cons for each. They are all 3-strand twist because of their ability to hold knots better. Some of these ropes can tend to unravel, so I would recommend always keeping a tight twist for better durability and limiting the stretchiness. The first two are natural ropes - the texture is rougher so it’s a good idea to use gloves when working with them. The other synthetic ropes are generally easier on the hands.

Hemp - the traditional rope, best for not stretching and holding knots. The main disadvantages: the rope is rough on your hands, they ‘shed’ material on the floor, your clothes, and into the air. Depending on the supplier, some hemp rope (like the one I bought, even after days of sun exposure and spraying with vinegar solution) smells so bad that I don’t want to handle it. Although I haven’t personally used them yet, the hemp rope sold at Miyamoto Unosuke Shoten and Asano Taiko are of high quality and don’t seem to have any offensive smell. They also seem to only carry the natural rope, with no dyed-color options. Asa is the Japanese word for hemp. I have been told that hemp shrinks over time, so that’s something to keep in mind.

Manila - a very inexpensive and easy-to-find alternative to hemp, it performs very well by holding knots and not stretching. Depending on the supplier, it can be rougher on the hands and shed even more than hemp. But it’s cheap and available everywhere. If there are higher-quality manila ropes out there, I would be interested in trying them out.

Kuremona - a synthetic rope that both Miyamoto and Asano carry. I would think that there are different types of kuremona, but my only experience with this rope is on the Edo Bayashi taiko made by Miyamoto. It stretches and slips more than the natural rope mentioned above, but it is within the acceptable range of performance. The advantages: the variety of colors available, and the rope feels nice in the hands.

POSH - a synthetic rope I recently became aware of and decided to try out. It stretches less and holds knots better than kuremona, but the main disadvantage is its stiffness. I would think that the rope will eventually soften, but I have only used it once. The lack of suppleness make it hard to get the slack out of knots before you tighten, and this doesn’t allow you full control of how much tension the rope creates on the drum heads. If this rope softens, it would be my top choice. I purchased this rope online at R & W Rope. It has been suggested that perhaps putting the rope through a wash cycle might soften it. The photo below shows the impressive array of POSH color options at R & W Rope. This photo was emailed to me by Ray, who was very helpful in helping me narrow down the choices. The online store shows less color selection, so you might need send them an email to order a specific color.

Vintage 3 Strand - another synthetic rope I recently learned about and purchased to try. This is softer and easier to handle than POSH, but with slightly less knot-holding ability. It also only comes in one color, a natural beige. Because it’s cheaper and easier to work with, I would place this rope slightly ahead of POSH in terms of performance. This was also purchased at R & W Rope.

The 4 ropes I tried back-to-back to compare

Rope samples from Miyamoto - five kuremona colors and hemp (far right)

POSH colors available at R & W Rope

Rope Diameter and Length

It makes sense to use the appropriate diameter rope for the size of shimedaiko you use. For the typical medium sized (2 or 3 chogake) drum, I think 10 - 12mm works well. A smaller drum might take 8 - 9mm and the biggest drums (4 or 5 chogake) could use 12 - 13mm, depending on the drum maker and rope type. In the US, 3/8 inch (9.5mm) rope is very common and easy to find. Thicker diameter is better for durability and less stretch but a rope too thick can be hard to work with. Take into consideration the depth of the body, how stretched the skins are already, and how large the holes near the rings are. For example, the Edo Bayashi taiko pictured below has a 9mm kuremona rope - it works fine, but I would prefer something slightly thicker for this drum. You can see that the holes are definitely wide enough for a bigger rope. I have learned that both Miyamoto and Asano sell a preset diameter rope for each shimedaiko size, which makes it simpler to order the appropriate rope for each drum size. However, you might want to ask for more detail about the material and diameter of the ropes so that you can choose one that best fits your needs. It’s common in Japan to use the traditional unit ‘bu’ (3mm) for rope, and for our purposes we would look for 3 or 4 bu (9mm or 12mm). But I’m pretty sure that other diameter ropes would be available in 1mm increments, and will continue my research to learn more about our options.

Miyamoto Edo Bayashi shimedaiko with 9mm kuremona

The taiko companies also seem to provide a set length for each shimedaiko size, but I think it would be possible to place a custom order. After the drum is tightened, I prefer to follow the common practice of winding the rope 3 times around before tying off. I have noticed that Kodo and Hayashi Eitetsu both wind the rope 2 times, so I can understand people using this method as well. For me, it’s like the martini olives rule - you should have an odd number, and 1 is too few (and 5 won’t fit). Because each drum will have differences in the length of rope required, I ordered 36 feet (11 meters) of rope for my testing and cut off the excess after tightening the drum for the first time. I feel more at ease knowing that I will have plenty of rope to work with, but you can certainly order less than this. If you are ordering from Miyamoto or Asano, it might be a good idea to ask about the set rope length and see if you can purchase your preferred length in addition to the diameter.

Whipping on the end of the rope

General Tips

1. It’s worth learning how to tie a proper whipping knot on the end of the rope to prevent it from fraying or unraveling. Tape can do the job, but it’s less aesthetically pleasing and it can come off with some pressure. A quick online search will give you many photo and video tutorials on how to whip the end of a rope.

2. Prioritize function over appearance. I have seen many drums with beautiful ropes that don’t work well at all, resulting in less than ideal sound and tightening performance. Instead of trying to find a rope that takes dye well (such as cotton) at the expense of function, search for rope that is already the color you are looking for within the category of acceptable performance.

3. Experiment to learn your individual preferences on material, diameter, length, and price. Then ask questions so that the supplier is sending you exactly what you are looking for. For example, I should have asked the salesperson about the smell of their hemp rope before ordering. Ask other taiko players, makers, and stores for detailed information so that you can build your base knowledge and find the best rope for you. I also found it interesting to learn about the wide the variation in pricing, so don’t forget to make note of the differences carefully. Let me know if you have any recommendations and I will add them to my list.

4. Learn proper tightening technique so that you value the performance of the rope. There are several different tightening methods that are commonly used. Choose one that works best for you and practice a lot. And boosting your ability to play the drum will increase your appreciation of the sound and condition of the skins over time.

5. Understand that your treatment of your shimedaiko can impact not just the sound, but also the longevity. A clamshelled shimedaiko will not last as long as a more evenly tightened one. And keeping a drum tightened all the time will result in a shorter lifespan than one that is loosened between uses. Of course, other factors like stick selection, playing technique, stand design, weather, and general handling practices will all affect how long your heads will last.

6. Links to suppliers:

Partially tightened Edo Bayashi shimedaiko by Miyamoto Unosuke Shoten

Complete set of Edo Bayashi instruments and accessories