Audio Recording Part 2: A More In-Depth Talk with Isaku Kageyama

This is Part 2 of my conversation series with Isaku Kageyama about audio recording gear and how to use it effectively in your home studio. In Part 1 we covered some basic information to get started, and you can find it here:

https://www.eienhunterishikawa.com/blog/isaku-home-studio-recording-gear

This time, we go further in depth and address some topics which had been requested over the past few weeks. Thank you to everyone who provided feedback and engaged with us through email and social media. I’m also very appreciative of Isaku’s willingness to sit down with me and spend so much time sharing his knowledge and experiences. Largely due to his help, I have been able to substantially improve my own audio recordings and gain a deeper understanding of important concepts and terminology over the past two months.

Isaku and I talked for quite a long time and I have split the audio into four downloadable parts. We readily admit that the sound quality of Part 1 was subpar, especially considering our conversation topic (the unfortunate result of a built-in recorder of a video call software with a name that does not start with z and rhymes with gripe). The Part 2 audio is much, much better.

If you would like to see a Part 3 in the future, please let us know. Feel free to send in topic requests or any questions you would like answered.

Links for the topics we discuss:

Isaku’s taiko mic comparison video

http://isakukageyama.com/best-mic-for-taiko-drums/

UnitOne virtual concert

https://youtu.be/uL2Fdsx_nO0

Isaku’s youtube channel - Garageband Basics, Fue EQ, Parallel Compression, Mixing, and More

https://www.youtube.com/c/IsakuKageyama/videos

Isaku’s directed study program

http://isakukageyama.com/directed-study-program-learn-taiko-music-production-and-more/

1. Taiko microphone test, audio samples, UnitOne concert audio

2. Tempo changes, mixing, midi keyboard and drum pads, recording fue, reverb, room importance

3. Potential income from recording, livestream concerts, click tracks, simplifying our playing

4. Isaku’s directed study online lessons, importance of feedback for effective learning

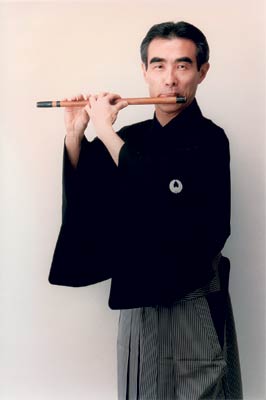

Isaku Kageyama is a taiko artist, well versed both in live performance and in the studio. His resume includes performances at venues such as Carnegie Hall and Lincoln Center, networks such as NBC, VH1 and BET, tours with the Japan Foundation, and residencies with The Pew Center for Arts and Heritage. He’s also an overall nice guy. :D:D:D

On stage and in the classroom, Isaku brings a breadth of experience performing and teaching both traditional and contemporary styles. A versatile collaborator in the studio, Isaku contributes to projects by bringing his extensive knowledge of composing, recording, and mixing to the table. When none of that is needed, his job is to make sure there is cold water in the fridge for everyone.

Isaku currently works as an instructor at Los Angeles Taiko Institute, performs with Asano Taiko US UnitOne, and records for virtual reality creators Rhythm of the Universe, and video game composers Materia Collective.

Formerly a principal drummer of Amanojaku, he holds a Bachelor of Music from the Berklee College of Music and a Master of Arts in Teaching from Longy School of Music of Bard College.

He is also a two-time National Odaiko Champion, becoming the youngest person to win highest honors at the Mt. Fuji Odaiko Contest in 2000, and Hokkaido in 2003.

From 2011-2014, Isaku was the resident instructor at Wellesley University and the University of Connecticut, and has held clinics at Berklee College of Music, Brown University, Rochester Institute of Technology, North American Taiko Conference, East Coast Taiko Conference, and Intercollegiate Taiko Invitationals.