Interview Part 3: Kaoru Watanabe talks Kodo, Odaiko, Chichibu Yataibayashi, and Miyake Jima Kamitsuki Kiyari Daiko

This is the third interview in my series with Kaoru. I highly recommend checking out the other two if you haven’t yet. It’s always a great pleasure to sit down with Kaoru and ask about his thoughts, experiences, and many interesting anecdotes. Beyond simply enjoying the conversation, I think we are providing important insights for anyone wanting to expand their knowledge and perspective.

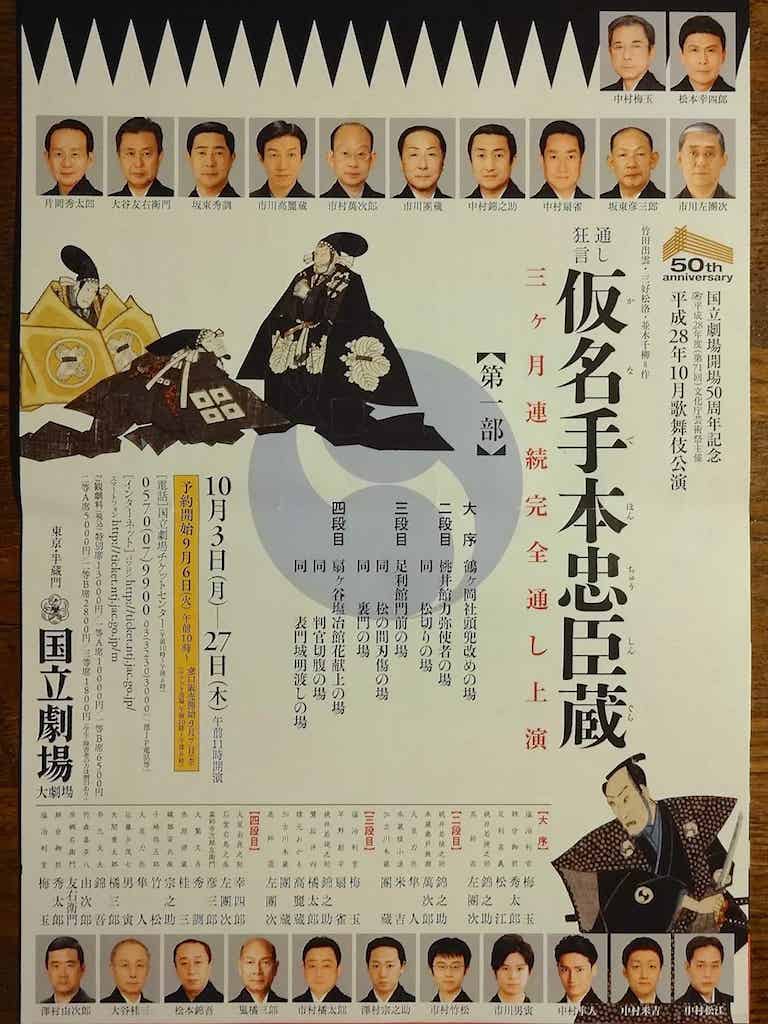

This interview happened exactly one week after I had attended the Kodo concert titled Warabe. The timing was coincidental but I took the opportunity to ask Kaoru about his time with Kodo, especially relating to the philosophy and culture around learning and performing traditional arts such as the ohayashi (music) from Chichibu and the Kamitsuki district of Miyake Jima. This conversation includes a lot of history and information that are invaluable in understanding Kodo as well as these traditional art forms. As we referenced near the end, we had also planned to talk about fue but ran out of time because of the depth and breadth of this discussion. We will get together for that topic in the near future. I hope you share my feeling of gratitude to Kaoru for taking the time to thoughtfully engage in these fascinating conversations. The supplemental material he provided (below) is a great resource for delving deeper into the topics covered in this interview. Feel free to send me comments, questions, or requests anytime.

Supplemental material from Kaoru:

Miyamoto Tsuneichi is a scholar who greatly influenced Den Tagayasu and recommended he set up the artisan village in Sado.

https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Forgotten_Japanese.html?id=q2EbG_NM1xwC&source=kp_author_description

The following are all dances I have learned from local practitioners. The first one is the one we're not allowed to perform, while the others we are. With Shishiodori, I not only did tours performing it, but I made the costume by hand! The Kakinoura Ondeko is the first of these dances I learned. The town between Kakinoura and Iwakubi that I couldn't recall is Odawara. A note that perhaps many people don't realize is that at Kodo we learn as much dancing as drumming. This is only a partial list of the dances (and fue/taiko/uta that goes with it) that I learned during my short time there.

Kurokawa Sansa, Morioka Prefecture

https://youtu.be/kw4JXAXMVCE?si=xmHflYyj34ptSvkm

Onikenbai, Iwate Prefecture

https://youtu.be/2FGN80g5ZU8?si=GJWD0We2m51Co-Ow

Shishiodori, Iwate Prefecture

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IXZTOoUiFUc

Kakinoura Ondeko

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RyI0yX1jtao

Iwakubi Ondeko

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WKpp2kKKTmE

Website

http://www.watanabekaoru.com

Youtube channel

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCfBL_1I2mRPcVK2gvyRAeNA

Instagram

https://www.instagram.com/kaorufue/

Kaoru Watanabe Taiko Center

http://www.taikonyc.com

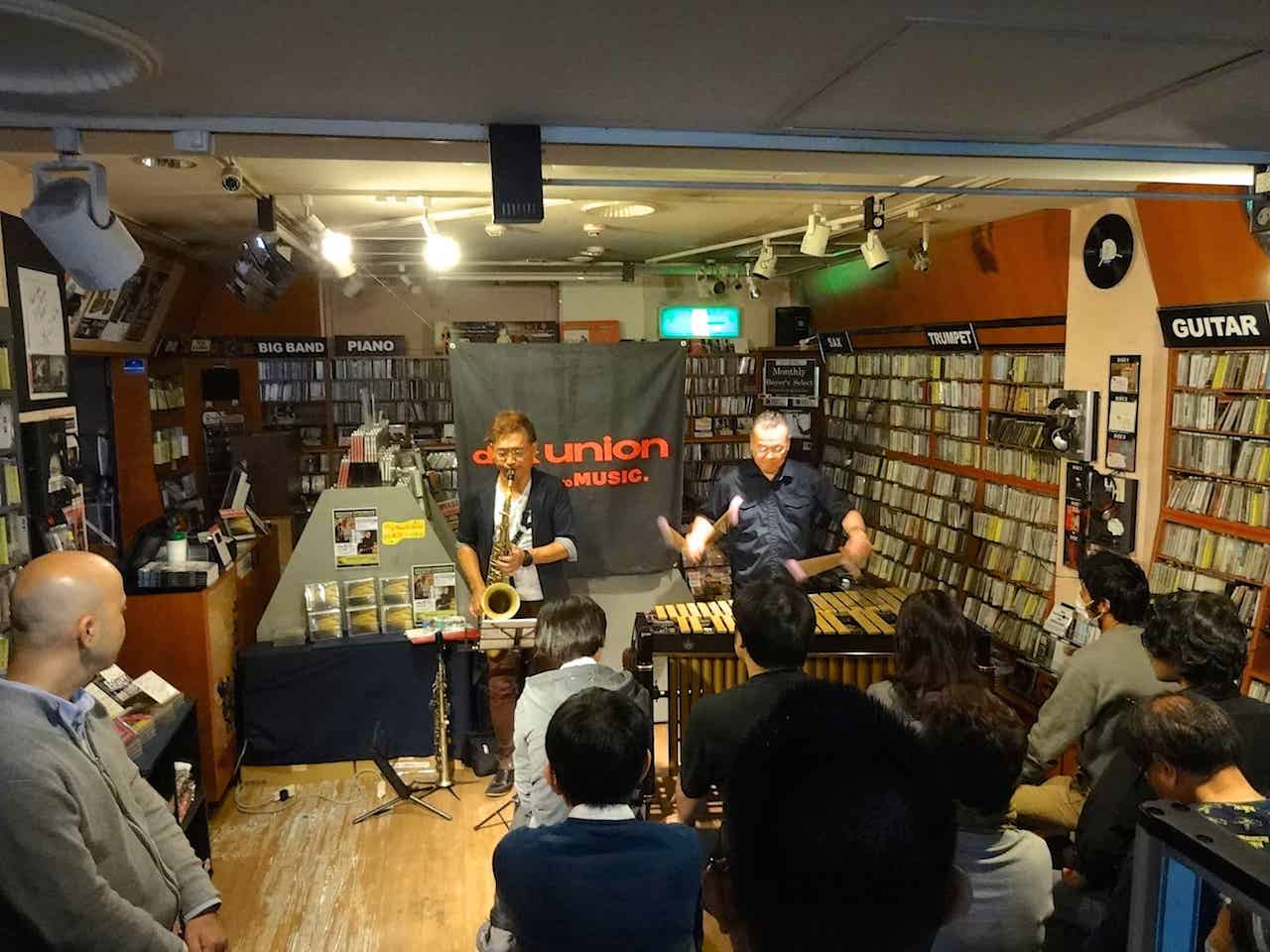

Acclaimed composer and instrumentalist Kaoru Watanabe's work is grounded in traditional Japanese music while imbued with contemporary jazz, improvisation, and experimental music elements. His signature skill of infusing Japanese culture with disparate styles on the shinobue flutes and taiko and other Japanese percussion has made him a much-in-demand collaborator working with such iconic artists as André 3000, Wes Anderson, Mikhail Baryshnikov, Laurie Anderson, Jason Moran, Yo-Yo Ma, Japanese National Living Treasure Bando Tamasaburo and Rhiannon Giddens. In 2024, Watanabe launched Bloodlines Interwoven, a festival celebrating music and diaspora, presented by Baryshnikov Arts and funded by the Mellon Foundation. Featuring a broad range of groundbreaking musicians, from Mino Cinelu, Nasheet Waits, Adam O'Farrill, Alicia Hall Moran, Layale Chaker, Martha Redbone, Du Yun, and many more, the festival was a paradigm-shifting musical exploration of cultural roots, identity, history.

Born to Japanese parents who were long-time St Louis Symphony Orchestra members, Watanabe began training at a young age, eventually graduating from the Manhattan School of Music, where he studied Black American jazz music. He then moved to Japan and became the first American to perform with and lead the internationally acclaimed taiko performing arts group Kodo. Acting as Artistic Director of Kodo's Earth Celebration festival, inviting such artists as Zakir Hussain, Giovanni Hidalgo, and other masters of music from across the globe, he first saw how profound cross-cultural collaboration could be: people who don’t share a common language can find ways to unite in musical conversation when done with a sense of mutual respect, open-mindedness, an open heart, and a desire to connect. In 2008, after ten transformative years in Japan, which left him deeply connected to his heritage and the land from which his parents came, he left Kodo. He returned to New York to weave together all the musical threads of his experiences.

Watanabe’s compositions draw lines between distant points—Japan and America, ancient history and modern politics, and Eastern and Western music. Looking for the sympathetic vibrations that emerge, he weaves together Buddhist chants reimagined as antipolice brutality protests, WWII-era ZERO kamikaze fighter planes, the Sengoku Civil War era, and the culture wars of today’s America. In his work, Watanabe introduces sounds from a distant past to the 21st century, expressing the many layers of his identity and culture. Watanabe has performed his compositions with such artists as Kodo, Yo-Yo Ma and the Silkroad Ensemble, and The Sydney Symphony Orchestra, with whom he debuted two pieces for shinobue, voice, taiko and orchestra at the Sydney Symphony Hall.

He acted as an advisor and was a featured musician on Wes Anderson’s Isle of Dogs, and he is featured on the Silkroad Ensemble’s Grammy Award-winning album Sing Me Home. He also created music for Martin Scorcese’s Silence and Netflix’s Ultraman: Rising, and perhaps his greatest accomplishment was providing the jazz flute stylings of the Pied Piper in Shrek 4ever After.

As an educator, Watanabe has taught courses at Princeton, Wesleyan, and Boston Conservatory and was an artist-in-residence at Loyola University. He has taught workshops across North and South America, Europe, and East and Southwest Asia.

Watanabe’s drums are provided by Miyamoto Unosuke Shoten, a mikoshi shrine and traditional instrument maker founded in 1861. His flutes are provided by Ranjo, a master craftsman based in Chiba Prefecture who makes instruments for many of the top musicians in Japan. One of the highest honors of Watanabe’s life is when Ranjo declared, “Watanabe possesses the greatest sound on the shinobue in the world.”